Joe Camel

Joe Camel, also known as Old Joe, was a controversial advertising mascot created by the R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company (RJR) to promote their Camel cigarette brand. Introduced in 1974 for a French advertising campaign, the character was redesigned for the U.S. market in 1988. He became a prominent figure in print media and merchandise, appearing in magazines, on billboards, and on branded apparel and collectibles.

In 1991, a study published by the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) highlighted concerns about the campaign’s appeal to children. Research revealed that Joe Camel was as recognizable as the Disney Channel logo among six-year-olds and that high school students were more familiar with him than adults. The study also noted a sharp increase in Camel’s market share among youth smokers. These findings led to legal challenges, including a lawsuit in California and a formal complaint from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), accusing RJR of unfair practices by allegedly targeting minors. While RJR denied marketing cigarettes to children, they ended the Joe Camel campaign in 1997 under mounting pressure from litigation and federal oversight.

| Names | Joe Camel, Old Joe |

| Gender | Male |

| Race | Camel |

| Occupation | Mascot |

| Origin | French Camel advertising campaign (1974) |

| Alignment | Mixed |

| Age | Unknown |

| Created By | R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company (RJR), Nicholas Price |

| Height | Varies |

| Weight | Varies |

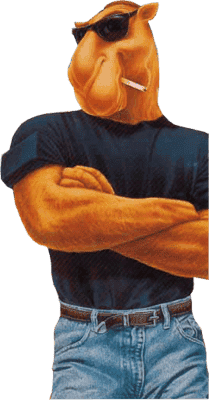

Appearance

Joe Camel is depicted as an anthropomorphic camel with a human-like body, lacking traditional camel features such as humps, hooves, or a tail. He has a muscular physique and a camel’s head, often dressed in masculine attire like tuxedos, T-shirts, or workwear. He is frequently portrayed in "heroic poses," surrounded by glamorous settings such as bars or in the company of women.

Personality

Joe Camel was designed to exude a "cool" and charismatic persona that embodied the aspirational qualities associated with the Camel brand. His personality projected confidence, charm, and an effortlessly suave demeanor. As a "smooth character," Joe Camel was depicted as the epitome of masculinity, often engaging in leisurely or exciting activities such as socializing in bars, lounging in tuxedos, or taking on adventurous and daring pursuits.

The character's persona was intended to align with the ideals of independence, sophistication, and approachability, appealing to adults as a figure of aspirational living. However, critics argued that Joe Camel's playful and cartoonish qualities also resonated with youth, leading to perceptions of him as a mischievous and fun-loving figure that contributed to the campaign's controversy.

Joe Camel’s "coolness" was his defining trait, crafted to make smoking seem stylish and desirable in a way that resonated with popular culture and consumer fantasies of self-expression and identity.

Biography

Background

Camel is the oldest cigarette brand in the United States, introduced by R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company (RJR) in 1913. The brand's logo originally featured a plain drawing of a camel, referred to as "Old Joe," designed by Belgian artist Fred Otto Kleesattel. The illustration was inspired by a real dromedary named Old Joe, part of the Barnum & Bailey Circus. The camel motif was chosen to reflect the use of Turkish tobacco, evoking associations with exotic Middle Eastern locales.

Camel cigarettes enjoyed significant popularity through various marketing campaigns, including a 1946 campaign claiming that doctors preferred Camels over other brands. By the early 1950s, Camel was the leading cigarette brand, but its market position declined by the mid-1980s. By 1985, Camel had dropped to sixth place, losing significant market share to Philip Morris’ Marlboro brand, which dominated with its iconic Marlboro Man campaign.

Concept and Creation

Joe Camel was first conceptualized in 1974 by British artist Nicholas Price for a French advertising campaign. The character was initially a suave, anthropomorphic camel with a focus on appealing to a European audience. Throughout the 1970s, this version of Joe Camel appeared in various international markets but had not yet debuted in the United States.

Joe Camel entered American advertising in 1988 as part of a campaign celebrating Camel’s 75th anniversary. The character was revitalized by art designer Mike Salisbury, working under the direction of McCann-Erickson New York, the primary ad agency for RJR. Salisbury’s brief was to create a mascot that could rival the Marlboro Man and appeal to younger audiences while evoking a "cool" and masculine image.

Initially, attempts to stylize Joe Camel as a character from old action films like those featuring Humphrey Bogart or Gary Cooper were not well-received, as audiences were unfamiliar with such figures. Salisbury reimagined Joe Camel with a look inspired by modern cultural icons like James Bond (Sean Connery) and Sonny Crockett (Don Johnson). Joe was given expressive eyebrows, slicked-back hair, and an aura of sophistication that combined danger and charm.

The campaign shifted focus to a hip, trendy lifestyle, featuring Joe in dynamic settings such as bars and parties, often surrounded by women and exuding confidence. The tagline "Smooth character" and the associated imagery resonated strongly, helping to reinvigorate the Camel brand.

The Joe Camel campaign was a marketing success, quickly transforming the public's perception of Camel cigarettes. The New York Times noted that it achieved a difficult feat by repositioning a brand rapidly. The campaign mitigated the impact of declining full-price cigarette sales, which had been dropping by 5-8% annually. Joe Camel became a central figure in Camel's advertising strategy, surviving multiple transitions between ad agencies, including McCann-Erickson, Young & Rubicam, and Mezzina/Brown Inc.

Despite its commercial success, the Joe Camel campaign became highly controversial, drawing criticism for allegedly targeting underage audiences. This controversy, combined with legal and regulatory pressures, led to the campaign's termination in 1997. Today, Joe Camel remains a notable example of both effective marketing and the ethical dilemmas of advertising in the tobacco industry.

JAMA Studies and Mangini Lawsuit

In December 1991, the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) published studies highlighting the Joe Camel campaign’s appeal to children. One study demonstrated that 91.3% of six-year-olds could correctly associate Joe Camel with cigarettes, nearly the same percentage that recognized the Disney Channel logo as Mickey Mouse. Another study compared recognition rates among high school students and adults over 21. High schoolers were significantly more likely to recognize Joe Camel (97.7% vs. 72.2%) and correctly identify Camel as the advertised brand (93.6% vs. 57.7%). The studies also noted Camel's market share among smokers under 18 had risen sharply, from 0.5% to 32.8% over three years.

These findings drew national attention, including that of San Francisco-based attorney Janet Mangini. In 1992, Mangini filed a lawsuit against RJR Nabisco, alleging the Joe Camel campaign targeted minors, citing a rise in Camel sales to teenagers from $6 million to $476 million over four years. RJR sought to dismiss the case, arguing only the federal government could regulate advertising, but a California court allowed the lawsuit to proceed in 1994. RJR's appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court to dismiss the case was rejected.

Criticism of the JAMA studies emerged as well. A 1994 Journal of Advertising article by five university professors criticized the studies for ethical and methodological flaws, including claims of biased results. Joe Camel’s designer, Mike Salisbury, also denied any intent to market to children, asserting that RJR deliberately avoided designs that could appeal to young audiences and styled Joe Camel as a 30-year-old character.

Federal Trade Commission Complaint

In 1991, the American Heart Association, American Lung Association, and American Cancer Society collectively urged the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to investigate RJR’s advertising practices. Following a two-year inquiry, the FTC initially decided in 1994 not to act due to insufficient evidence of federal law violations.

However, after President Bill Clinton appointed new FTC leadership in 1997, the case was reopened. On May 28, 1997, the FTC accused RJR of deliberately targeting youth through the Joe Camel campaign, describing it as an "unfair practice" under Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act. The FTC’s findings alleged RJR had sought to attract "first usual brand" smokers, many of whom were minors, and argued that children could not reasonably understand the risks of smoking.

End of the Campaign

By March 1997, Joe Camel had already been removed from advertisements as RJR prepared for federal litigation. On July 10, 1997, RJR officially terminated the Joe Camel campaign, just weeks after the FTC’s formal complaint and amidst broader legal and regulatory pressures. This included a $368.5 billion settlement with 40 states to recover costs from tobacco-related health care, as well as a voluntary agreement among tobacco companies to cease using cartoon characters in advertising.

RJR replaced the campaign with the "What you're looking for" campaign, which returned to using the original camel illustration from Camel's packaging. As part of a settlement with Mangini's lawsuit, RJR agreed to pay $10 million to fund youth-targeted anti-smoking initiatives in California. Interest in Joe Camel memorabilia surged following the campaign’s closure, cementing its place as a controversial chapter in advertising history.

Legacy and Influence of the Joe Camel Campaign

The Joe Camel campaign is suspected to have inspired similar advertising strategies for other products. In late 1991, Brown & Williamson tested a revival of their penguin mascot, Willie, for the Kool cigarette brand. Willie had originally appeared in Kool ads between 1933 and 1960, but the character's return was noted by The New York Times as likely influenced by the Joe Camel campaign. Anti-smoking organizations criticized the test campaign, seeing it as an attempt to replicate Joe Camel’s appeal.

Similar accusations of targeting youth were leveled at other industries. In 2004, anti-drinking groups criticized Anheuser-Busch for its "Bud-weis-er" frogs campaign, and advocates against childhood obesity targeted Ronald McDonald and other mascots for promoting unhealthy foods. Legal proceedings in these cases frequently cited the precedent set by Joe Camel’s controversy as part of their arguments.

In 1996, the anti-consumerism magazine Adbusters published a parody subvertisement titled "Joe Chemo." The illustration depicted Joe Camel as a bedridden, terminally ill cancer patient, highlighting the health consequences of smoking. The parody was developed in collaboration with psychology professor Scott Plous, who first proposed the concept, and was shared in the advertising industry magazine Adweek.

Retrospective Assessment

Academics have analyzed the long-term effects of the Joe Camel campaign, with mixed conclusions. A 2010 paper in the International Journal of Advertising found that while the campaign initially brought significant consumer attention to the Camel brand, the subsequent negative publicity likely reinforced anti-smoking attitudes. The study noted that Joe Camel was ultimately less successful than Philip Morris' Marlboro Man, which achieved a stronger cultural and market presence.

Additionally, the paper pointed out that brands like Newport reached a comparable market share and similarly young demographic without the use of a mascot or spokesperson, suggesting that Joe Camel’s presence may not have been as critical to Camel’s success as initially perceived. While the campaign is remembered for its controversy, it also stands as a cautionary tale about the potential risks of aggressive and ethically questionable marketing strategies.

Trivia

- Joe Camel was initially created for a French advertising campaign in 1974 before being adapted for the U.S. market in 1988.

- The character's suave appearance in the U.S. campaign was inspired by James Bond (Sean Connery's expressive eyebrows) and James "Sonny" Crockett from Miami Vice (Don Johnson's hairstyle).

- Joe Camel's original design lacked camelid traits such as humps, hooves, or a tail, emphasizing his anthropomorphic and "cool" human-like qualities.

- RJR once offered promotional merchandise through "Camel Cash," where customers could redeem points for Joe Camel-branded items, including watches, mugs, and even shower curtains.

- Critics accused Joe Camel's nose of being drawn in a phallic shape, implying subliminal messaging about smoking and virility. This claim was denied by the character’s designer, Mike Salisbury.

- Joe Camel became a frequent target for parody, including Adbusters' "Joe Chemo," which reimagined him as a bedridden cancer patient to critique the health impacts of smoking.

- Joe Camel's campaign was controversial enough to be cited as legal precedent in cases against advertising mascots perceived to target children, such as Anheuser-Busch's "Bud-weis-er" frogs and Ronald McDonald.

- Following the campaign’s end, Joe Camel memorabilia became sought after by collectors, gaining a nostalgic yet controversial legacy.

- The campaign's closure led RJR to revert to the original plain camel design featured on Camel cigarette packaging.